- Home

- Roberts, Lorilyn

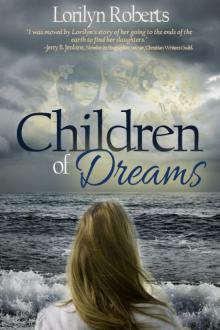

Children of Dreams, An Adoption Memoir Page 4

Children of Dreams, An Adoption Memoir Read online

Page 4

One morning we went out on what is called a “drift dive.” A drift dive is where the diver jumps off the side of the boat and the current carries him either on a harrowing rollercoaster ride or a meandering, leisurely tour.

Drift diving was my favorite kind of dive because I didn’t have to worry about where the dive boat was. I was never adept at using a compass under water. With drift diving, the dive boat follows the “bubbles” and picks up divers when they float to the surface.

On this day I jumped off the boat and went down like a weighted anchor. Rather than floating lazily in the current, I found myself within a few seconds at eighty feet deep. I was quite impressed that I beat everyone else down. Usually my dive buddy would have to wait on me because scar tissue in my left ear made it difficult for me to equalize. All alone, I moseyed around for a few minutes waiting for the other divers to float down beside me, but no one showed up. It was a beautiful dive and I didn’t want to cut it short by heading to the surface, but divers aren’t supposed to swim alone in the ocean. Actually, it’s a foolish thing to do, so reluctantly, I went to the surface.

When I poked my head out and looked around, the only boats in sight were way off in the distance. The dive boat had left me behind, following the other divers on their drift. I was all alone in the Gulf of Mexico with a 40-pound tank on my back in the middle of nowhere. I knew it would take an hour for the others to finish their dive and decompress, depending on how deep they went. They would have to get back on the boat and discover I was missing. I figured it would be at least a couple of hours before I would be rescued if I was ever rescued at all.

The first hour floating all alone in the ocean I remained calm. The second hour gave way to waves of fear and panic as I began to seriously ponder my desperate situation. Suppose the dive boat never found me? My life passed before my eyes. What a horrible way to die. I wasn’t ready. “Please, God,” I cried out, “don’t leave me out here in the Gulf. I want to live.”

I contemplated what few options I had, which were none, and thought about how many sharks might be lurking. What was underneath my dangling feet and would I ever be found? I floated helplessly for hours with a forty-pound tank on my back breathing though my snorkel in the middle of nowhere.

Had God not saved my life that day in the Turneffe Islands for something far more wonderful than I could have imagined? Would I let Satan rob me of my joy of adoption by filling my heart with fear? I was tired, hungry, and emotionally drained. Satan knew I was vulnerable.

Only God could take away my slavery to the fear that paralyzed me. As fear’s grip on me let go, God held me in His arms, much like a mother would hold her infant daughter, and spoke silently to my heart, “I love you.”

At last, I peacefully dozed off. I awakened early the next morning feeling strong and courageous, anxious to get on the road and ready for an incredible adventure. Never again in the years since have I doubted that Manisha was supposed to be my daughter. I was filled with peace, had a good night’s rest, and was ready for whatever storms lay ahead.

We would be leaving at 5:30 a.m. to travel to the Janakpur District to have documents signed by the CDO. It would be a long and arduous journey.

Chapter Seven

…let us go up to the mountain of the Lord

Micah 4:2

I ate a light breakfast at the small restaurant inside the Bleu Hotel, consisting of tea and toast. I made sure everything was packed for the trip, including nuts, bananas, and candy bars.

“You have to feed everybody for the trip,” Ankit said. “There will be five of us.”

I triple checked that I packed all six sets of documents and that everything was in order. I was anxious to get going and was impatient for him to show up.

At last, he arrived at the hotel wearing jeans, a light jacket, and a red cap, along with the driver in a white van. It was barely light outside and quiet. The streets were empty and the stores had not yet open. I was surprised that Manisha and her father weren’t in the van.

“We’ll pick them up on the way out of town,” Ankit reassured me. I wondered if Manisha had anything to eat. If not, she could fill up on all the snacks I brought. I showed Ankit the food and we both climbed into the van.

Wearing a blue dress and white blouse, I was glad to be spared another motorcycle ride. I loaded a fresh roll of film in my Nikon camera and made sure I had plenty of money to pay the driver. My paranoia prompted me to check once again that I wasn’t missing any documents.

I looked forward to getting out of Kathmandu for the day (the dusty air was bothering my sinuses) and seeing the beautiful countryside and towering Himalayan Mountains.

“Be sure to bring your camera,” Ankit said. “You will get a good view of Mount Everest if it’s not cloudy.”

It took a while to travel through downtown Kathmandu. The sun was just beginning to cast its first rays of light over the streets and buildings, and I could see shadows of people in the distance.

I was startled to see so many standing on the edge of small streams by the road brushing their teeth. The water appeared muddied from the rains. I had noticed a toothbrush and toothpaste in the hotel room when I met Manisha. For a country that didn’t seem to use toilet paper, it surprised me that anyone would brush their teeth.

Ankit exited the van and walked into the hotel to retrieve Raj and Manisha. Eventually they made their way out and I saw that Manisha was wearing the same dirty blue outfit from the previous day. My heart ached to put something new on her. I imagined how beautiful she would look in the pretty pink dress and checkered blue top I brought her.

They climbed into the van and Raj smiled at me. Manisha was quiet and did not want to sit beside me today. She stayed with her father. I asked Ankit to ask Raj if she had eaten.

“A glass of milk,” he replied. I felt badly as I had eaten more than she had.

After a while we left Kathmandu far behind. Old brick and concrete buildings were replaced with scenic flowers and grass, with clumps of trees dotting the countryside. Every so often we passed young lads shepherding cows on the side of the road. Grass took over where there had been dirt and scenic rolling hills followed one after another in an orderly, rhythmic pattern. The panoramic vistas, the motion of the van, and lack of sleep made the trip seem dream-like, but I was jolted back to reality by the start and stop of the steady stream of vehicles ahead of us and those coming from the opposite direction.

As the day went on, the road deteriorated into one bump after another. Eventually the two lane road narrowed to one, and the rolling hills out of Kathmandu became gigantic mountains. The road wound like a child’s slinky, and I wondered at every turn if someone approaching from the other side would hurl us into the abyss below. Around every bend I heard horns honking, ours or another car, and sometimes both.

Our destination was the Dolakha District of the Janakpur Zone, the town of Charikot. Our trek took us from Lamusagu, which was about 47 miles outside of Kathmandu, to Lamosagu Jiri, another 27 miles. Then we traveled to Khaktapur, which had been the main trade route for centuries between Tibet/China and India. That accounted for the high volume of traffic. Its position on the main caravan route made the city rich and prosperous by Nepali standards.

The scenery was spectacular. Never had I seen such incredible beauty. We were surrounded by mountains in every direction as far as the eye could see. I wondered how such incredible beauty could coexist side by side with some of the most destitute people in the world. If it weren’t for the children who were so malnourished, with protruding bellies and red hair, I could have been totally absorbed in the magnificence of the Himalayans, but the children were heartbreaking.

Nepal’s per capital income was only $180 per year, one of the lowest in the world and the lowest in South Asia, where the average per capital income was $350 per year. Of its eighteen million inhabitants, half lived in abject poverty.

The next town was Dolalghat, where we crossed a long bridge over the Tamakosi River, whi

ch was about six hours from Kathmandu.

We subsequently came upon the Indrawati River where a large group of people were gathered, facing an unusual construction of wood in the middle of the river. It was still smoldering from being burned.

“What is that?” I asked Ankit.

“They are having a funeral. It is the Hindu custom to burn the dead body over a river.”

I hated thinking about Manisha’s birthmother in that way.

“Just down the river a little further,” he continued, “at Chere, we recently baptized about twenty people.”

I chose to focus on the baptism of believers in the river rather than the burning of dead bodies for the rest of the trip to Janakpur.

We traveled along the Bhotekosi River and crossed that river at Khardi Sanopakhar, Dada Pakhar, and Thulopakhar, which was close to Ankit’s village.

Then we came to Sildhunga, Mude, and Kharidhunga, which were nine thousand feet above sea level. After that, we traveled through Boch, and finally arrived at Charikot, which was the district headquarters of the Dolakha District in Janakpur, arriving in the late afternoon. Januk was the name of a famous king and “pur” means city or town. It was a historical holy city.

As we were driving along and the road became nearly intolerable to ride on, I looked at Manisha and wondered how she could not get sick. I shouldn’t have thought it because soon thereafter, she threw up. Her father tried to hold her out the window as we were driving until the last of the milk landed on the road instead of in the van. Maybe it was a good thing she only had milk for breakfast. She looked dreadfully unhappy. If only I had brought a change of clothes for her.

After a long while, we stopped. Everybody got out and walked in different directions. I wasn’t sure what I was supposed to do.

Ankit glanced back at me and said, “It’s time to go to the bathroom.”

I convinced myself I didn’t need to go. Maybe if I waited a while, we would come to a restaurant somewhere, like a McDonald’s, and I could go then. Of course, there was nothing but mountains around us in the middle of the Himalayans. I just wasn’t ready to head for the bushes.

“I don’t need to go,” I lied, waiting in the van while everyone else disappeared. Plus, I didn’t bring any toilet paper. D___ that toilet paper. As I looked out the window, a female monkey in season scurried by the van.

I had a few moments to be captivated by the view. There was nothing around me but mountain peaks adorned in various shades of blue and green. I wondered how there could be so much evil, so much violence, so much wrong with the world when so far from all of that, God’s handiwork stood tall and majestic. It was like God had painted the sky, the mountains, the rivers and waterfalls with a touch of heaven, a glimpse of what awaits us beyond heaven’s gates. The mountains and the trees and fields would have burst forth in praise if it were possible.

The beauty was like a tiny thread woven through a tapestry where time and sin had ravaged the perfect nature of all things; one lone thread that promised redemption, a taste, if you will, of the magnificence of God’s original creation.

Within me a sense of longing arose, a burning desire to partake of the beauty of our heavenly home that God is preparing for us. Whatever my eyes have beheld here, that my senses have been awakened to, so much more so will it be there. Paul wrote in I Corinthians 2:9, “… as it is written: ‘No eye has seen, no ear has heard, no mind has conceived what God has prepared for those who love Him.’”

Eventually everyone returned to the van. Manisha and her father climbed in sitting to the left of me in the back. She had warmed up to me again and I was able to hold her for a few minutes as the van gathered speed on the half paved, half dirt road.

Her clothes now were not only dirtied and soiled, but smelled of sour milk. Her shoes, riddled with holes and far too small, had been tossed into the back of the van.

It was still hard for me to believe she was going to be my daughter. I would rest easier when we were in the air over Kathmandu headed toward Los Angeles. That seemed an eternity away right now. There was lots of talk going on but since everyone spoke in Nepali, I didn’t know what was being said except for the occasional translation by Ankit.

We continued to travel for a long time passing through small villages where we had to make numerous stops to register with an official who sat in a hut beside the road.

A couple more hours passed and no McDonald’s or Wendy’s showed up on the radar, so I thought before things got desperate, I better do something. There were too many jolts of the van on the bumpy road to wait too long.

Ankit asked the driver to stop and a few minutes later he pulled the van over to the side of the road.

“Is this okay?” Ankit asked.

“Well, I don’t have any toilet paper.”

He looked back at me in amazement. “Why didn’t you bring toilet paper?”

“I didn’t know I would need toilet paper. I just thought we would stop somewhere at a restaurant and go.”

“We’re out in the middle of the Himalayan Mountains!”

There were no restaurants out here, just mountains and small make shift homes with poor, needy children running around taking care of cows more dead than alive, and one monkey in heat. No five star hotels, let alone anything resembling a Western style restaurant.

“We’ll stop at the next village and I’ll try to get some,” Ankit said.

Guys just don’t get it, I thought. Or maybe I really am a soft American.

Later we made a brief stop at a little shack in a small village. Ankit ran in and purchased some toilet paper, quickly came out, and handed it to me through the window. I tried not to look embarrassed and avoided eye contact with everybody. I was just glad to have my toilet paper.

We proceeded to drive along the road and every few minutes the driver slowed down and Ankit would look back at me with a questioning look, “Is this a good place to stop? Do you want to stop here?”

“Yeah, this is okay,” I said at last. I just wanted to be done with it.

I climbed out of the van and started heading down a little path off to the side of the road carrying my toilet paper mumbling to myself, “I am not a soft American girl. Gee, they probably do this all the time.”

After doing my deed I headed back up the trail and saw that everyone else had left the van. Fortunately nobody went my way, so I just waited until everybody returned.

By now we were all hungry so I handed out some of the snacks that I brought and we began to munch on them. It was about 3:00 or so in the afternoon when we finally arrived at the CDO’s office.

We pulled off the road to a large open area in front of a two story, white concrete building with brown shutters. A red and white Nepali flag hung limply from a flag post out front. There were a few children and men milling about. It was quiet and peaceful, unlike the bustle of activity in Kathmandu. The whole area was surrounded by mountains off in the distance.

As I looked toward the east, Ankit said, “Just over those mountains is China.” It felt like the ends of the earth. I took a few pictures and then followed Ankit up the flight of stairs to the second story of the CDO’s office. Manisha and her father followed closely behind. I clasped my documents under my arm and held on to them nervously.

“You need to be friendly with the CDO and talk to him when he asks you questions.” I could tell Ankit was also nervous.

Appearing in front of a government official who wielded such power over my future was certainly out of my bailiwick. I tried to focus on the matter at hand but my heart was racing, wanting it to be done. My throat was so dry I wasn’t even sure I could respond to any questions he might ask me.

As we stood in the doorway, the room appeared very dark. We were motioned in and I found an empty seat several feet from the door. As I waited for my eyes to adjust, I gazed through the window. The Himalayan Mountains in the distance seemed to symbolize the huge hurdle in front of me in the guise of this official.

Manisha sat besi

de me. One exposed light bulb with wires crisscrossing the ceiling provided the only lighting. Old wooden chairs lined the bare walls. I felt like I was starring in a movie as I sat in the dusty, dingy office of the CDO of Dolakha, Nepal.

A man in his early 30’s, the CDO was dressed in a green suit with a pointed little cap on top of his head. It was hard to comprehend how a man on the other side of the world could have such incredible control over my destiny except God had given him that authority.

My thoughts flashed back momentarily to all that preceded this defining moment in my life. As a child my parents told me I was born under a cloud. My husband chided me, “Is this another one of your sad stories?”

“I don’t love you anymore,” my partner spitefully responded one night after I presented him with evidence that he was seeing another woman. I remembered the wine bottles and cheese that I uncovered in the garbage after being away for a few days visiting my family.

I replayed scenes of the long hours I worked as a court reporter putting him through medical school. I recalled the night he contacted the police after I confronted him in his office at the hospital. Two weeks after our divorce was final, the other woman gave birth to his child. I was devastated and hurt. Only a loving God could help me to recover and begin a new life in Him. Would God give me a chance to redeem the years the locusts had eaten?

A few years after my divorce, I received a letter from World Vision, an evangelical organization that sponsors children in Third World countries. The beginning of the letter, dated February 13, 1993, read: “Over 150 million children worldwide are trapped by hunger, sickness, poverty, and neglect.” I took the letter and put it on my refrigerator. Someday, I thought, I am going to adopt a child from another country. How and when, only God knew.

The letter ended with the quote from Proverbs 13:12 (LB): “Hope deferred makes the heart sick, but when dreams come true at last, there is life and joy.”

Children of Dreams, An Adoption Memoir

Children of Dreams, An Adoption Memoir